Here at Mint Diagnostics, we have Prof. Anna Whittaker of the University of Birmingham, one of the world’s leading experts in stress science, as a scientific advisor so we got together with her at the beginning of the year to get her thoughts on how Mint Diagnostics’ real-time cortisol test could impact her work and stress monitoring in general.

So, Anna, let’s start with the fundamentals. What is stress?

Stress can be measured as what stressful life events happen to us as well as our perceptions of these events and our ability to cope, for example, bereavement, losing our job, or divorce, and these ‘stressors’ have been shown in much scientific research to have a negative impact on our physical and mental health. For example, in my research the stress of bereavement has been related to not producing enough antibodies after vaccination, so that we are less able to fight off ‘flu, and poorer functioning of immune cells key to fighting bacterial diseases like pneumonia. These direct links with effects on the immune system are one of the ways in which stress can affect our health.

So, stress affects not just our mental health but also our physical health?

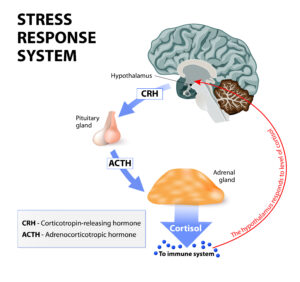

Yes, to understand this, we need to know how stress gets inside the body; this happens through our body’s stress response systems. Stress is perceived in the brain by our cerebral cortex which communicates with other brain systems involved in emotion processing. These communicate via our autonomic nervous system to our adrenal glands which results in the production of neurotransmitter hormones such as adrenaline and noradrenaline which have direct effects on our organs, blood vessels, muscles and glands, including the cardiovascular system so it can be felt in the rapid beating of our heart. A slightly slower stress response is also activated through the brain but results in outputs from our hypothalamus and pituitary gland which communicate with our adrenal glands and results in the production of the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol plays a role in metabolism and regulation of our immune system, but can result in dampening of our immune responses if high levels are sustained for a period of time. Usually these stress response systems have mechanisms to prevent them overshooting, but if we experience prolonged stress or continuous stressful events, our system starts to show wear and tear and can reset into a pattern of producing continuously high or low levels of stress hormones, both of which are not optimal for our health.

How do our cortisol levels change when we’re stressed?

The stress hormone cortisol has a daily rhythm of levels in the body with a swift rise on waking, relatively high levels in the morning which drop throughout the day but more slowly in the afternoon towards lower levels in the evening, so often what we see in response to stress is not just a change in levels but a change in the pattern throughout the day, such as a blunting of the initial rise upon waking or raised evening levels associated with ongoing stress.

Cortisol can also rise in the short-term in response to stressful situations, and the extent of that short-term increase can differ depending on individuals’ underlying stress levels and overall health. However, what happens to us in terms of stress is not the only factor predicting our bodily response and resulting health, but also how we appraise or psychologically respond to stressful experiences, and our belief in our ability to cope with them. As a result of all these variations in cortisol levels and stress levels, and their changes over time, being able to assess stress using portable measures can give us more useful and detailed information than the use of questionnaires or biological measures at a single time point.

We need to be careful with the interpretation of biological as well as self-reported assessments of stress, as there are so many factors which can affect both our cortisol and stress levels. However, being able to assess the rhythm of cortisol across the day with a portable fast and easy to analyse method will allow us to research far more thoroughly the links between our day to day experience of stress and changes in our biological rhythms and levels of stress hormones.

Do you see portable salivary cortisol tests as making a big impact in your research?

Absolutely. Portable cortisol measurement also has many advantages over standard laboratory assays which we use at the moment and which require specialist equipment and facilities, as well as the inconvenience of using and storing standard saliva collection receptacles. As long as the accuracy and sensitivity of cortisol measurements is comparable to current state of the art laboratory assays, this type of portable monitoring will also allow more valid and easier measurement of changes in individuals’ daily stress levels than one-off questionnaires measures relying on recall over a longer time period, or not measuring changes over time. Further, being able to monitor changes in perceived stress and cortisol levels goes beyond many portable stress/health measures which tend to focus on heart rate. Cortisol monitoring will be able to give us a more complete picture of the longer term effects of stress such as chronic stress alterations that momentary changes in heart rate cannot do. Consequently, I believe this type of measurement has great potential for enhancing research as well as helping individuals or organisations to monitor their own stress levels.